The story of the 1906 Lower East Side school riots

June 27th, 1906 was an otherwise uneventful Wednesday morning in the Lower East Side. In the neighborhood predominantly peopled by Jewish immigrants from Germany and Russia, the kids were off at school and their parents were going about their daily routines.

It was around 9:30 that morning that the rumor first began to circulate—throughout the neighborhood schools, doctors and nurses put in place by the Russian Government were instructed to begin cutting the throats of the children and were going to bury the bodies in the playground. Panic set in and quickly spread. Distraught mothers began running through the streets to one of eight schools in the area where the majority of their children attended classes.

Thousands of women descended on the buildings, yelling so that their children might hear, so that anyone around might help. They threw rocks at the windows and broke through locked doors to save their children from what seemed a certain death. The teachers, caught completely off guard, did the only thing they could think of—they dismissed classes. As the some 25,000 school children streamed from the buildings unharmed, the panic subsided.

The rumor was ultimately proven to be untrue. In all likelihood it was started by one of the many unqualified “doctors” that preyed on the poor immigrant populations throughout the city. But to understand how the rumor started and why the panic was so immediate is to understand how two otherwise disparate elements were at play in the community.

The first involves the city’s Department of Health’s push to bring better healthcare to the public schools. The second taps into the very real fears that the immigrant population was dealing with, both in the countries they left behind and the new one they were trying their best to become a part of.

A dire rumor

In 1897, the Department had begun to send doctors and nurses to the city’s public schools to examine and treat the students. By 1906, it was fairly common for doctors to have diagnosed a child, alerted the parents, and, in many cases, treat the student for a host of illnesses and afflictions. Such was the case in June 1906, as some 80 children throughout the Lower East Side were selected to have their inflamed tonsils removed. The parents were notified and, due to the fact that the majority of families couldn’t otherwise afford the procedure, the Department decided to have the school doctors perform the operations.

Enter the quacks. The free healthcare that the Department was doling out was putting a dent in their business and they were none too pleased. It’s thought that one of their number started the rumor in the hopes of driving their potential patients (and their patients’ money) back into their seedy offices. It was, without a doubt, a foolish and reckless prank. By all accounts, however, the riots that took place were well beyond the intended effect the pranksters were looking for.

But what was it about the rumor that brought about such a visceral reaction?

They were powder waiting for the fuse

To better understand why the mothers in the neighborhood reacted as they did, it’s important to contextualize the world as they most likely knew it. The majority of the predominantly Jewish population of the Lower East Side had immigrated to the United States only five to ten years prior to 1906. They’d come from cities across the Russian empire—cities like Kishinev, Odessa, and Bialystok. seeking safe harbor as much as anything else, as eastern Europe had become a hotbed of anti-Semitism, persecution, and abject violence. In addition to a number of massacres of Jewish people throughout Eastern Europe in 1903 and 1905, news of another pogrom occurring in Bialystock had hit papers only weeks before the riot.

And the New York they’d relocated to was a fairly unfriendly place for a lot of immigrants—due in large part to the native New Yorkers’ perception that the immigrants were refusing to assimilate*. It’s a challenge that a lot of immigrants surely face. At what point are you to let go of your history and completely embrace your new homeland? And should you ever have to relinquish those connections totally? It’s that difficult balancing act that many of the Lower East Side residents were likely trying to navigate.

So, here was a population that was largely feeling unwelcome in the U.S. and had only recently fled abusive governments. In that context, the rumor that their children were being killed by government officials doesn’t seem to be as wild as it first appeared.

In the aftermath, the vast majority of news outlets took general swipes at Jewish people and reported the riot as being one borne from ignorance and as another example of why the immigrants needed to better assimilate. Only a few papers appeared to recognized the connection between the horrors the immigrants had left behind and the current rumors of the same.

As for the school-children, there was some hand-wringing about whether the procedures should continue, but ultimately doctors did continue to offer free health services to the mostly underprivileged students. And interestingly enough, the doctor (a John J. Cronin) that reported on these procedures and the riot briefly ran afoul of then President Teddy Roosevelt on the ever-prickly subject of race suicide, a topic we’ll dive into in a forthcoming post.

*There is much to be said about what constitutes a “native” New Yorker, considering that today’s native is more often than not yesterday’s immigrant. For the sake of this piece, “native” refers to the population that saw themselves as more established and treated others as such. This isn’t to condemn or condone their behavior, but rather to illustrate how the world looked for both parties in a city that has been (and is) rife with change.

[Sources]

The American Monthly Review of Reviews – April 1907

Brooklyn Daily Eagle – 29 June 1906

Nowhere is this personified better than in the Mystic Success Club, the brainchild of two New Thought leaders Helen Van Anderson and Hubert A. Knight (two amazingly interesting people in their own right). Promising “health, wealth, a long, useful and blessed career,” the club worked as a sort of pyramid scheme / self-help-by-mail series.

Nowhere is this personified better than in the Mystic Success Club, the brainchild of two New Thought leaders Helen Van Anderson and Hubert A. Knight (two amazingly interesting people in their own right). Promising “health, wealth, a long, useful and blessed career,” the club worked as a sort of pyramid scheme / self-help-by-mail series.

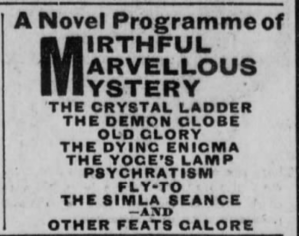

Needless to say, seances were all the rage. And, if you were on the hunt for a place to talk to your dead relatives, you could do a lot worse than Boston. It very well could have been that reputation that brought a Dutchman named Billfledler to a Union Park Street séance on an otherwise unassuming Sunday night in April 1904. It’s unfortunate, however, that his conversation with his deceased wife Gretel was so rudely interrupted by a full-on police raid.

Needless to say, seances were all the rage. And, if you were on the hunt for a place to talk to your dead relatives, you could do a lot worse than Boston. It very well could have been that reputation that brought a Dutchman named Billfledler to a Union Park Street séance on an otherwise unassuming Sunday night in April 1904. It’s unfortunate, however, that his conversation with his deceased wife Gretel was so rudely interrupted by a full-on police raid.